Chiese di Milano

Project by Giorgina S. Paiella

An interactive map tour of the churches of Milan. Click the “Visit” button below to tour the project interface, and scroll below for a discussion of project origins, features, and reflections.

Chiese di Milano: Origins

When I arrived in Milan, discovering a city anew, I found myself spending most of my time visiting and exploring churches. On each outing, excursion, and passeggiata in the city, it was impossible to not find myself at the doorstep of one of these stunning churches, and I was captivated with reverence for their beauty and history. The living history of these churches is something that I wanted to pay homage to in some way, so I decided to create a visualization project to map the churches of the city.

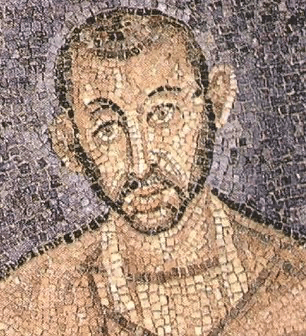

As I attended mass, I was particularly drawn to the beauty and tradition of the Ambrosian Rite. The Ambrosian Rite is a Latin liturgical rite named after Saint Ambrose (Sant’Ambrogio), bishop of Milan in the fourth century and doctor of the church. The liturgy of the Ambrosian Rite has unique features that distinguish it from the Roman Rite. Though I do not list these features comprehensively here, they include certain additions and omissions to the liturgy, its own cycle of readings, a longer Advent and later start to Lent, different liturgical rites, an Ambrosian chant tradition distinguished from the Gregorian chant, and unique clerical vestments. The Ambrosian Rite lives on throughout the Archdiocese of Milan. The rite was originally widespread throughout the provinces of Milan, Lecco, Monza, Varese, parts of Como, and some areas in the provinces of Pavia, Bergamo, in addition to parts of Ticino and Lugano in Switzerland. Over time, some communities that previously adhered to the Ambrosian Rite have since transitioned to the Roman Rite. Most of the Archdiocese of Milan currently celebrates the Ambrosian rite, with the exception of a number of cities and communes within the diocese, such as Monza and Treviglio. Saint Ambrose remains particularly important to Milan as the patron saint of the city, and he is honored on December 7th each year as part of the city-wide celebrations of the Feast of Saint Ambrose (Festa di Sant’Ambrogio).

While Milan perhaps does not seem like the natural first choice for examining Catholic church history—typically overshadowed by Rome, the seat of the Vatican and the Holy See—I believe it is important to center the city for its rich religious and cultural history. Milan was essential to the history of my favorite saint, Saint Augustine (Sant’Agostino), who was inspired by Saint Ambrose to convert to Christianity. Augustine was teaching rhetoric in Milan and went to hear Saint Ambrose, then bishop of Milan, preaching. Augustine was particularly drawn to Ambrose’s eloquent style of speaking, but Augustine also credits Ambrose with inspiring in him a new understanding of the Christian faith.

As he recounts in his Confessions, one day in 386, Augustine was in a garden in Milan with his friend Alypius. Augustine had been grappling with the question of the source of evil and a particular struggle with bodily lust, and he knew that he had to repent from his current lifestyle in order to become a Christian. As he struggled in agony about how to overcome this internal battle that had been plaguing him for some time, Augustine withdrew from his friend Alypius and resigned himself to solitude in the garden. He threw himself to the ground under a fig tree and cried out to God in despair, “O Lord, how long? How long? Will you be angry for ever? Do not remember our age-old sins”. . . “Why must I go on saying, ‘Tomorrow . . . tomorrow’? Why not now? Why not put an end to my depravity this very hour?”1 Augustine recounts that he then heard the voice of a boy or girl chanting over and over again, “tolle lege, tolle lege,” (“take up and read, take up and read”).2

Upon hearing the child’s voice, Augustine picked up the scriptures and silently read the passage on which his “eyes first lighted,” Romans 13:13, a passage which spoke directly to Augustine’s struggle with sin: “Not in dissipation and drunkenness, nor in debauchery and lewdness, nor in arguing and jealousy; but put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh or the gratification of your desires.”3 “I had no wish to read further, nor was there need,” Augustine writes, “No sooner had I reached the end of the verse than the light of certainty flooded my heart and all dark shades of doubt fled away.”4 Augustine was baptized by Saint Ambrose a year later during the Easter Vigil, on Holy Saturday, April 24th, 387, in the baptistery now underneath the present-day Duomo di Milano.

Features of Chiese di Milano

I have included in this first iteration of my project a mapping of several categories of Catholic religious structures in Milan.

In my initial compilation of structures to include in my project, I have included basilicas, churches, chapels, oratories, civic temples, and sanctuaries. Each of these structures have different designations and significations. For example, basilicas are buildings within the Catholic church that have special designation for ceremonial purposes, and I have mapped all of the minor basilicas in Milan. The category of “major basilica” belongs only to the four great churches of Rome, all of which are located in the Diocese of Rome. All of the basilicas in Milan have the designation of “minor basilica.”

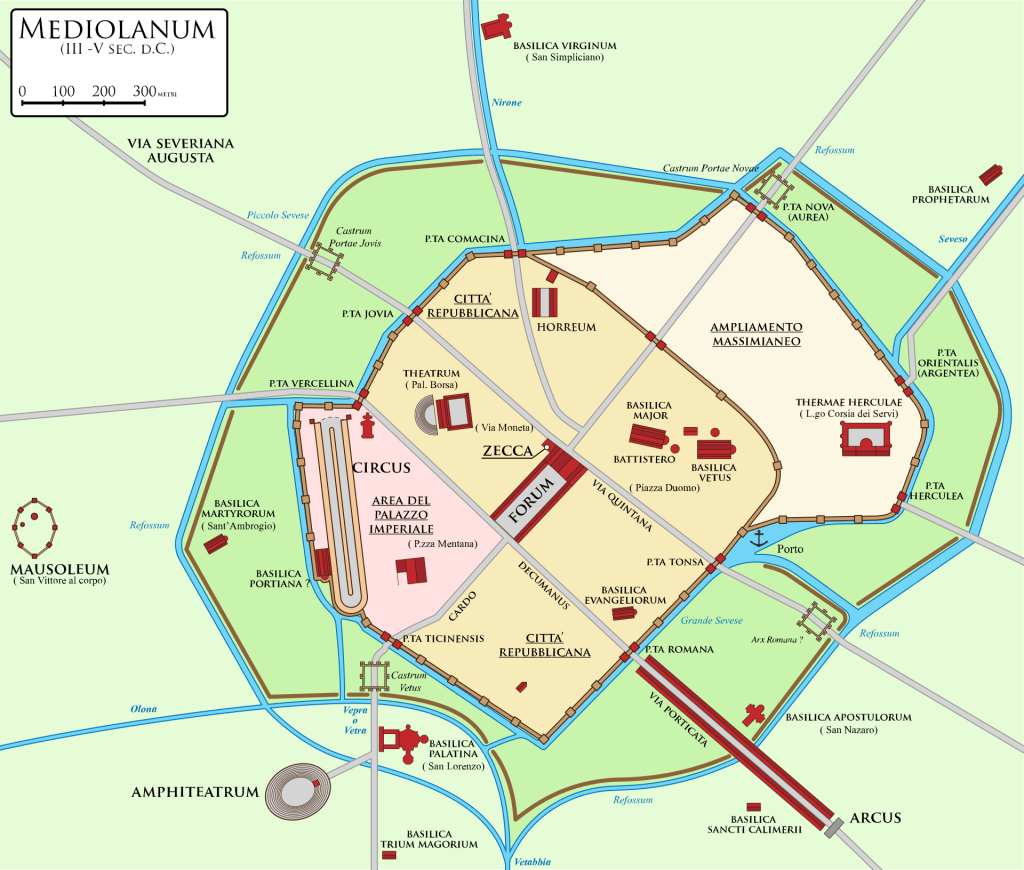

My project is structured as a map tour, which means that points can be explored freely and not in a set guided order. Should one wish to follow the map tour sequentially, I have ordered my project as follows. I begin with the Duomo di Milano, the cathedral that serves as the seat of the Chiesa di Milano and the Archbishop of Milan. The layout of the city radiates out from the Duomo, as it was the most central site in Mediolanum, the ancient city where present-day Milan now stands. The first cathedral located on the current site of the Milan Cathedral was dedicated to Saint Thecla and was called basilica nova or basilica maior (“new basilica” or “major basilica”), and later, the Basilica di Santa Tecla. Construction of the basilica began in 350 and was completed by 355, and the Basilica of Santa Tecla was demolished in 1461 to allow for the construction of the Duomo di Milano. I then include all of the basilicas (basiliche) in the city, followed by chapels (capelle) and churches (chiese), cloisters (choistri), a civic temple (civico tempio), monasteries (monasteri), oratories (oratori), and sanctuaries (santuari), all listed in alphabetical order within each category.

All of the churches included in my project have fascinating and rich histories, and some have special historical significance in the context of early Christian history of the city. These include the early Ambrosian churches of Milan (basiliche ambrosiane) built according to a program of construction under Sant’Ambrogio when he served as bishop of Milan from 374 to 397 A.D. The most important churches constructed in this period were the basilica martirum (Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio), basilica apostolorum (Basilica di San Nazaro in Brolo), basilica virginum (Basilica di San Simpliciano), and basilica prophetarum (Basilica di San Dionigi). Only the first three basilicas still exist in Milan. The fourth, basilica prophetarum—or Basilica di San Dionigi—was demolished in 1783 to make room for public gardens.

Several of the churches included in my project belong to certain church communities and networks. One example is the Comunità Pastorale “Santi Profeti” (the pastoral community of the holy prophets), which includes San Babila, Santa Maria della Passione, San Pietro in Gessate, San Francesco di Paola, and Santa Maria di Sanità. Another example is the Comunità Pastorale dei Santi Apostoli, which includes Sant’Euphemia, Santa Maria al Paradiso, San Francesco di Sales, San Calimero, and Sant’Antonio Abate.

I have included descriptions for all of the churches included in my project in English and Italian. I have included a link to the website of a given structure when available because these parishes can provide the most comprehensive information on the history of a given church. If no website is available, I do not include a link. These links, in addition to detailing the history of a given religious structure, provide information about mass times, oratories, and other pastoral activities for further exploration.

In addition to including Catholic Churches in this mapping project, I also include Catholic Churches that have been granted to various Orthodox Christian denominations, including the Coptic Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, Bulgarian Orthodox, Romanian Orthodox, and Russian Orthodox Christian communities of Milan. I make this choice for several reasons. The first is to reveal the dynamic history of churches in the city and to trace their history from initial construction to current liturgical use by various faithful communities. I also made this choice because it feels particularly in the spirit of the church during the time of Sant’Ambrogio, a moment in history when the Catholic and Orthodox churches were united as one church. Orthodox Christianity is essential to the history of Christianity and the history of the church, and it remains a critical pillar of the Christian faith. But perhaps most importantly, I include these churches to demonstrate the rich Christian traditions and cultural communities that reside in Milan and enrich the culture and diversity of the city. These Orthodox churches not only serve as centers of worship, but also cornerstones and gathering spaces for the diverse ethnic, racial, religious, and ethnoreligious communities that call Milan home.

A number of churches included in my project are former sites that are now ruins or deconsecrated churches that are currently used for secular purposes. I denote structures that fall into this category with an “ex” label after their name in my project interface, and I include a description that indicates the history of the structure and its current use or status in the present day. Cloisters (choistri) presented a unique issue, as most cloisters in the city have been transformed for non-religious purposes in the present day. Several monasteries and cloisters included in this project, for example, presently serve as museum and gallery spaces, public event spaces, and movie theaters. I was initially hesitant to include structures that are no longer used for religious purposes for this reason, but I have decided to do so because these structures are historically significant, are situated at a fascinating crossroads of history, religion, urban planning, and architecture, and sometimes still feature religious art and relics in their gallery and exhibition spaces.

Of course, because Milan is centuries old and structures and spaces are constantly being transformed, it is impossible to map every former significant religious site or their associated ruins. A city poses a particular challenge in this case, as many historical churches were demolished over time to make way for housing developments and to create public spaces. I have included the most significant of these archaeological sites, but many structures no longer exist, have been replaced by other structures, or are documented only in archived architectural plans or historical photographs. Limitations on space and new construction have also resulted in a particular urban character and appearance to more modern churches in the city (such as Chiesa di San Francisco di Sales), which vastly differ from historical churches and are necessarily adapted to building regulations and populated residential areas.

Visualizing and Mapping Chiese di Milano

As I created my project, there were some necessary choices that arose from questions and limitations inherent to visualization and curation. I originally set out to map all of the churches within the outer ring road of Milan, below.

I collected data on all of the churches located within the boundaries of this outer ring road and created a spreadsheet based on my map searches for churches, basilicas, chapels, sanctuaries, and monasteries within this area. After this compilation process, I started to map these churches on the Esri StoryMaps map tour platform. Quite unexpectedly, as I added my 100th mapping point to my project’s map tour interface, I received an error message that StoryMaps was limited to 100 map tour points in the non-enterprise version of the platform. A redirection was therefore necessary. While this was disappointing to discover, especially deep into the collection and creation process, I decided to go back to the drawing board and limit the churches in this first iteration of my project to Zone One of Milan, which is delineated by the following boundaries, below.

This narrowing process resulted in a project that was slightly more limited than I would have initially preferred, especially because it does not allow for mapping in some important neighborhoods in the city, which is why I did not originally set out to limit the project to these boundaries and parameters. Considering the limitations of the platform, however, I had to limit breadth in favor of completeness within a smaller boundary of the city and parameter of neighborhoods. The only exceptions that I made beyond Zone One of the city were to include basilicas (as I have mapped all of the basilicas in the city), and for certain important structures notable for their particular historical significance or uniqueness (for example, the Oratorio Santa Maria di Lourdes, a Marian Shrine modeled after that of Lourdes).

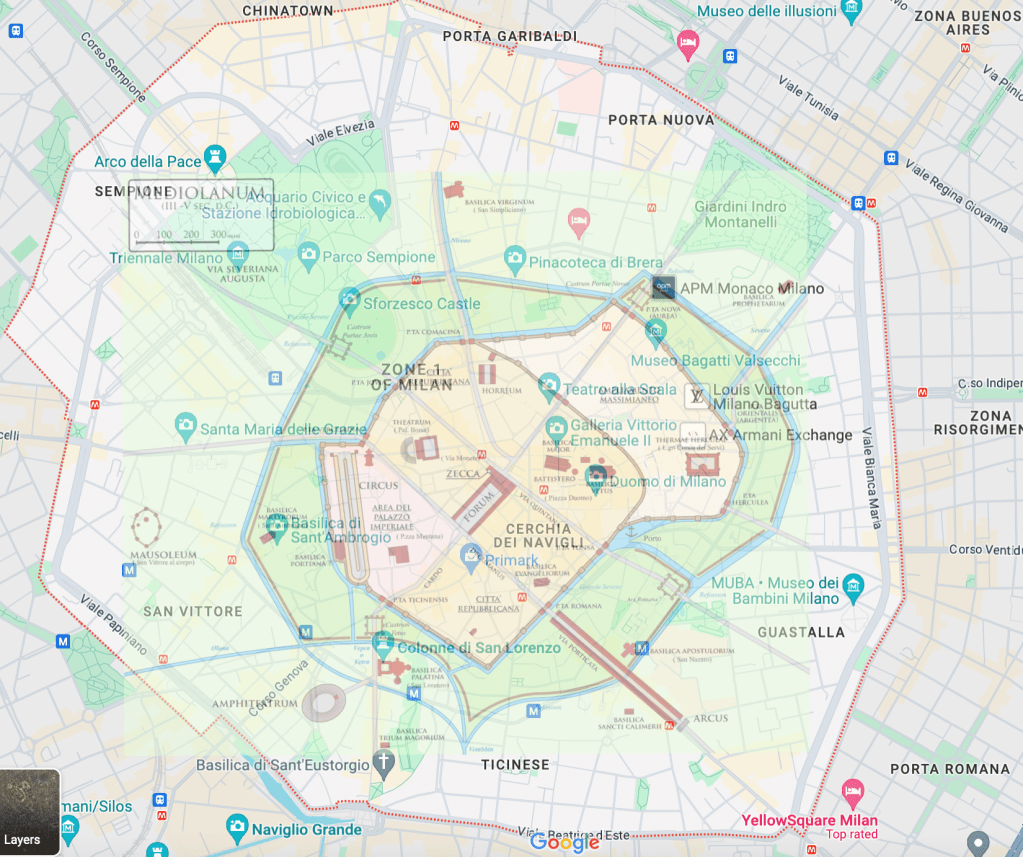

What I originally perceived as a limitation, however, ended up more closely aligning with the historical boundaries of Mediolanum, the ancient city where present-day Milan now stands. The city became an important city in Northern Italy under the Roman empire, and it became the capital of the Western Roman Empire under Emperor Maximian. Mediolanum is also particularly important to the early Christian history of the city, as it is the city from which Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, which granted tolerance to all religions within the Roman empire. Featured below is a depiction of the boundaries of Mediolanum between the 3rd and 5th centuries A.D.

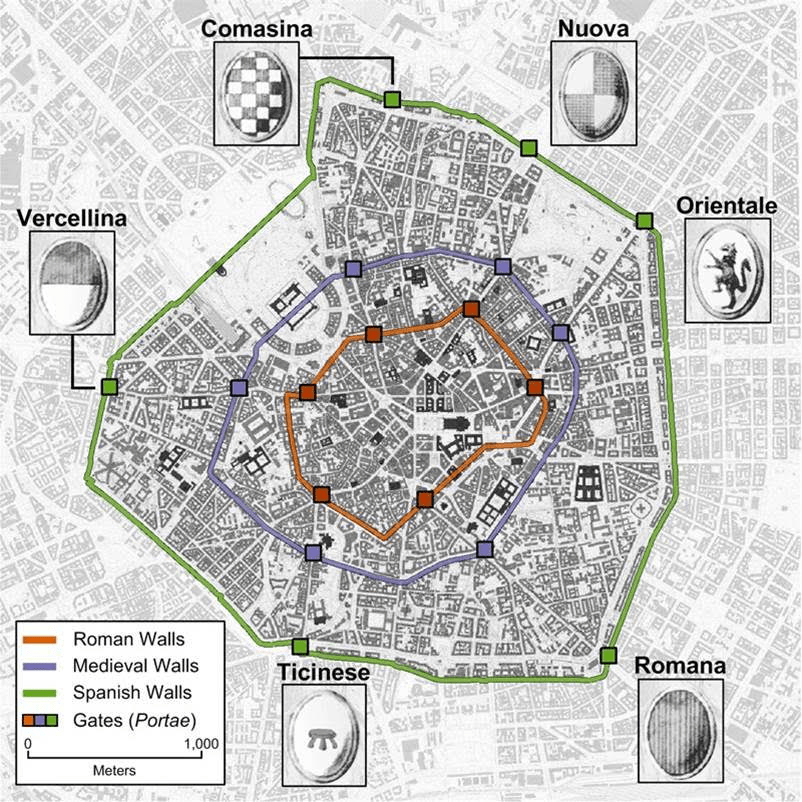

Below is a map of Mediolanum as the city and its borders evolved historically. The walls of the city had six main gates: “Porta Romana,” “Porta Ticinese,” “Porta Vercellina,” “Porta Orientale,” “Porta Jovia,” and “Porta Cumana.” “Porta Romana” and “Porta Ticinese” are now used interchangeably to refer to later systems of city walls (such as the Spanish walls), and the remains of these systems remain throughout parts of the city. The wall systems and boundaries differentiate different time periods and reigns, such as the Roman, Medieval, and Spanish walls enforcing the city.

Here is a map that I have created superimposing a map of Mediolanum from the 3rd to the 5th centuries upon a modern-day map of Zone One of Milan.

The vast majority of the basilicas and churches in the city tended to fall within these boundaries, which makes sense considering the history of major basilica and church construction in the paleochristian period. This includes the four Ambrosian churches (the three that still remain in the city: Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio, Basilica di San Simpliciano, and Basilica di San Nazaro in Brolo), other early churches like Basilica di San Lorenzo and Basilica di San Calimero. These basilicas appear in the map that I have created, below, that triple superimposes a map of Roman Mediolanum from the 3rd to the 5th centuries, important historical sites from Roman Mediolanum like the Roman Forum, Circus, and Imperial Palace, and a current map of Zone One of Milan.

All mapping and visualization projects inherently result in reduction, and this is not unique to my project. By reducing any real-world object to a data point, there are always accompanying issues of omission and reduction. I found this to be especially true of a topic as lively as the church, which does not exist in structures alone but in things invisible as well as visible—of faith, history, communities, stories, and living parishes—that are impossible to represent in their full vibrancy. I have opted to include in my project external photos of the structures that I map, though this of course does not do full justice to one of the most beautiful aspects of these churches: their interiors. As all church (and architecture) lovers will attest to, the interiors of these churches are remarkable and feature relics and artworks therein. Many of the churches in Milan house frescoes, artworks from famous painters, and historical relics that are centuries old.

A large number of these churches and other structures have undergone numerous restorations, remodels, and expansions throughout their histories, and the present structure of a given church—including the current façade and interior—does not always track these transformations over time. I therefore include descriptions to detail some of these histories and the renovations and alterations that have led to the present-day appearance of a given structure. One of my favorite aspects of religious buildings are the stories of their evolution over time. Many of these churches include a blend of artistic and architectural styles, structures, and schools from various time periods that are not always consistent, but tell a unique and entirely individuated story that is also shaped by historical events and the circumstances of various religious communities and parishes. While some original sites and structures are not preserved in their entirety, there are countless relics, frescoes, and ruins that provide a time capsule of—and entry-point into—a given moment in history.

I hope that my project can serve as a site of exploration of this rich history. It is my belief that the digital can serve as a launchpad for exploration, but—as with all beauty in the world—things must be felt and experienced in the flesh to lend them full vibrancy. The church cannot simply be reduced to a structure, but is a living experience of faith and beauty experienced on all sensory modalities, from the scent of historical churches—an ineffable blend of centuries-old wood, incense, and stone—to the sound of an organ that echoes up to the apse. While there will always be limitations inherent to these types of representations, I approach my project as an attempt to pay homage to my experiences with faith in the city and the beauty that is to be found. As Italo Calvino writes in Invisible Cities, “You take delight not in a city’s seven or seventy wonders, but in the answer it gives to a question of yours.”

- Augustine, Saint, Bishop of Hippo. The Confessions. Translated by Maria Boulding. Augustinian Heritage Institute, 1997, p. 206.

Augustine notes that these are not the exact words he uses to address the Lord, but he roughly paraphrases in his Confessions. (“Many things I had to say to you, and the gist of them, though not the precise words, was: ‘O Lord, how long’…”)

↩︎ - “Tolle lege” translates to the command, “take up and read.” This phrase is sometimes more colloquially and loosely translated as, “pick it up, and read, pick it up, and read,” as the phrase appears in Boulding’s translation.

↩︎ - Romans 13:13-14.

↩︎ - Augustine, Saint, Bishop of Hippo. The Confessions. Translated by Maria Boulding. Augustinian Heritage Institute, 1997, p. 206. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.